Welcome to Qustodio. The global leader in parental control and wellbeing apps.

Family Zone has joined forces with Qustodio to help give parents better visibility of their children’s online activities and balance screen time.

Trusted by 5 million users worldwide, Qustodio helps children grow with a healthy approach to technology and protects them from online risks.

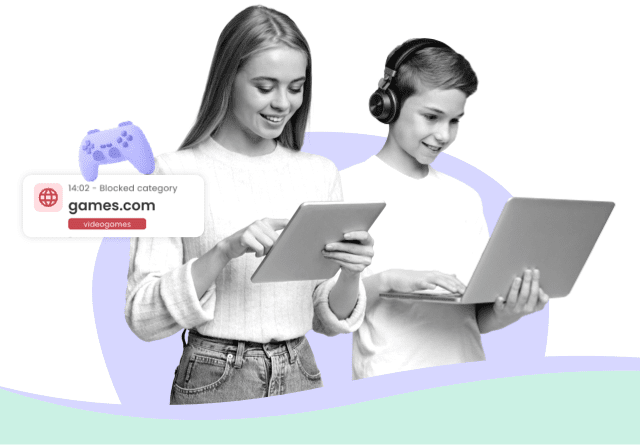

Parenting in the digital age made easy

Keep your child safe online

Ensure your child’s digital activity is balanced and risk free

Supervise the way you want

Filter websites, set time limits, block apps, get reports, and more

Build positive digital habits

Help your child develop a healthy relationship with technology

It takes just a few minutes to get started

Discover more about Qustodio’s features below

Qustodio gives you the best parental control and digital wellbeing features in one place

Keep your kids’ screen time safe and balanced on every device

Filter content & apps

Create a safe space for your kids to explore and play online

Monitor activity

Stay involved in your child's digital life

Log in to the real-time dashboard from any device at any time to check your child’s digital activity and adjust your settings. Easily view their activity timeline, browsing history, YouTube views, screen time and more.

Set time limits

Healthy families start with healthy habits

Help your child avoid screen addiction, ensure better sleep routines, and preserve family time by setting up consistent time limits and screen-free periods. Top up or reduce their device use limits as much as you want, when you want.

Locate family

Know where your kids are at any time

Spot your child on the map to know where they are and have been. Save most visited places like school and home and get peace of mind by receiving notifications when they arrive or leave those locations.

Track calls & SMS for Android and iOS

Catch predators and cyberbullies the moment they strike

Detect suspicious contacts by seeing who your child exchanges calls and messages with. Read the texts they send and receive, plus set a list of blocked phone numbers.

Get reports, alerts & SOS

Get all the info you want at the touch of a button

Receive detailed daily, weekly, and monthly reports of your child’s online activity straight to your inbox. Real-time alerts mean you’ll know as soon as they try to access blocked websites or are in trouble.

Real stories from parents

“Qustodio gives me the peace of mind that I have been looking for to ensure my kids are safe online.”

“With Qustodio, I don’t have to struggle to balance my daughter’s online independence with her safety.”

“We’re a highly digital family but we really value screen-free time—Qustodio helps us get that balance.”

Featured in the media

“Everything you need to know about your kid’s screen time is beautifully displayed on Qustodio’s online dashboard.”

“Makes device monitoring easy for parents.”

“From YouTube monitoring to a panic button for kids away from home, Qustodio covers just about everything.”

“Most complete parental control application available.”

Getting started is easy and takes just a few seconds

Create your FREE account now

And enjoy a trial of our Premium features